Today we discuss how atom probe tomography can address climate change issues. Is there anything the atom probe can’t do? More seriously, each new climate change report brings more concern. Greenhouse gas emissions are linked to atmospheric warming, with several contributors. Surprisingly, steel production is a major factor in carbon-release to the environment. Steel is essential in industries like energy, construction, and automotive, with over 2 billion tons produced annually.

[1] [2] We can’t function without it, but we must envision a future where steel production is sustainable, without relying on fossil fuels.

While steel supports sustainability through lightweight design and efficient turbines, its production remains a significant carbon emitter.

[3] Currently, 70% of steelmaking involves smelting iron ore in blast furnaces using carbon, generating 3 billion tons of CO

2 emissions, or 7% to 9% of all human-caused greenhouse gases. To meet climate goals, steelmaking’s CO

2 emissions must be cut by at least 50% by 2050, with further reductions towards zero emissions, according to the World Steel Association.

[4] Achieving this requires embracing carbon-lean production technologies to reduce CO

2 emissions by 80%. The steel industry needs breakthrough technologies and a bold call to action, as outlined by Worldsteel and the International Energy Agency’s Iron and Steel Technology Roadmap

[5] [6].Scientists are exploring ways to produce “green steel” by reducing steelmaking’s carbon footprint. This includes direct CO

2 removal at the atomic scale.

A promising method is hydrogen-based direct reduction of iron (H-DRI), which replaces carbon with hydrogen as a reducing agent. Significant progress is being made in understanding H-DRI and hydrogen-based plasma reductionoth are being explored as a sustainable route to mitigate CO2 emissions, where the reduction kinetics of the intermediate oxide product FexO (wüstite) into iron is the rate-limiting step of the process,” says Professor Dierk Raabe of the Max Planck Institute for Sustainable Materials in Düsseldorf, Germany. “The total reaction has an endothermic net energy balance. Reduction based on a hydrogen plasma also offers an attractive alternative.

A promising method is hydrogen-based direct reduction of iron (H-DRI), which replaces carbon with hydrogen as a reducing agent. Significant progress is being made in understanding H-DRI and hydrogen-based plasma reductionoth are being explored as a sustainable route to mitigate CO2 emissions, where the reduction kinetics of the intermediate oxide product FexO (wüstite) into iron is the rate-limiting step of the process,” says Professor Dierk Raabe of the Max Planck Institute for Sustainable Materials in Düsseldorf, Germany. “The total reaction has an endothermic net energy balance. Reduction based on a hydrogen plasma also offers an attractive alternative.

We sat down with Professor Raabe in a Nature Research webcast for some of his thoughts on the impact that green steel could have for reducing carbon emissions, and how

atom probe tomography (APT) is a key part of greener energy production. You can see a glimpse of the LEAP 5000 system at MPI-Sustainable Materials in Figure 1. Let’s take a closer look at how atom probe has a central role to play in this research.

Figure 1: Dr. Raymond Nutor, Alexander von Humboldt Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Sustainable Materials, operates the LEAP 5000 system. Atom probe provides insight into the reduction efficiency of greener methods such as hydrogen plasma reduction (HPR).

Figure 1: Dr. Raymond Nutor, Alexander von Humboldt Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Sustainable Materials, operates the LEAP 5000 system. Atom probe provides insight into the reduction efficiency of greener methods such as hydrogen plasma reduction (HPR).

Why research green steel?

DR: Much of our greenhouse gas emissions come from the combustion of fossil fuels for energy, from agriculture, manufacturing and construction, the latter of which dominates.

We produce about 2 billion tons of steel annually, much more than all the other big ones like aluminum, nickel and titanium combined. Steel is beating them all in quantity, but also in energy consumption and CO

2 emissions. Steel represents the top material class when it comes to sheer volume and environmental impact. This problem is not coming to an end; it is actually growing. A forecast from the OECD shows that by the year of 2060, we will have doubled our consumption of many of the raw materials that lead to immense CO

2 emissions. An example is the consumption of iron ore, which will more than double. Figure 2 shows a clear depiction of energy consumption for different manufacturing processes, including the production of iron ore, copper ores, and other metals.

Figure 2: OECD HIGHLIGHTS. Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060 – Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequence. [8]

How atom probe helps understand reaction kinetics through nanoscale compositional analysis

DR: In primary steel synthesis, iron is reduced from ores by carbon, a process that contributes 30% of global CO2 emissions from the manufacturing sector and thus qualifies it as the largest single industrial greenhouse gas emission source. The use of hydrogen for iron oxide reduction, also known as direct reduction of iron, or H-DRI, has been explored as a sustainable mitigating route for decades and is an attractive alternative.

However, reduction kinetics in hydrogen metallurgy are still relatively slow and not well understood. Some rate-limiting factors of the underlying reactions are determined by the microstructure and local chemistry of ores, particularly during the final step of the reduction of the oxide wüstite into metallic iron, which is much slower than the preceding reduction of the other oxides (hematite and magnetite). The total reaction has an endothermic net energy balance, and it will require much more research to understand these processes. This includes continuing the study of microstructures and composition at the atomic scale. (See Figure 3.)

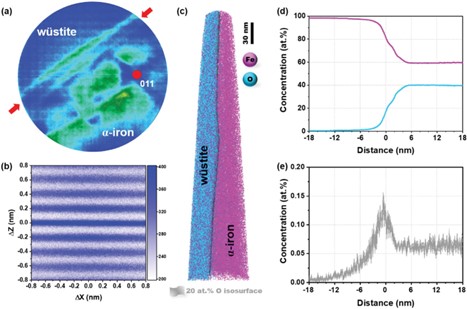

There are macroscopic studies on the reduction of iron oxide exposed to gas mixtures that include hydrogen. Again, key aspects that influence reduction kinetics — microstructure, nano-chemistry, porosity, pressure conditions, reductant mixtures and more — require further research. We know that all these lesser-known parameters and mechanisms act on micro- and even near-atomic length scales, with significant influence on transport and reaction kinetics. Thus, the next level of insight requires direct observations at these small scales, probing both structure and chemistry. [3] An example of how we can investigate these structures with APT is shown in Figure 3, revealing the interface of the wüstite phase with iron. Atom probe is one of the only techniques that can provide 3D compositional information at the nanoscale that may help to inform reaction kinetics.

Figure 3: 3D atom probe maps of (a) before and (b) after the direct reduction of as-received hematite iron ore (hematite), from a region about 1 mm below the pellet surface. Pink and cyan dots in the 3D reconstructions represent individual Fe and O atoms, respectively. (c) A reconstructed 3D atom map acquired from as-reduced ore. Iso-surface of O at 25 at.% (cyan) represents the interface between α-Fe and the wüstite oxide. The inset is a 3D atom probe map of a 5 nm thin slice. [3]

Why is hydrogen plasma reduction (HPR) a viable hybrid method?

DR: In direct reduction with hydrogen, the reduction kinetics of wüstite, the intermediate oxide product, into iron is the rate-limiting step. Reduction of hematite using a hydrogen- containing plasma is another attractive option. Researchers have studied the evolution of chemical composition and phase transformations in several intermediate states. The key is an optimized input mass- arc power ratio, which must be carefully controlled during exposure of the molten oxide to hydrogen plasma.

In hydrogen-plasma based reduction the micro- and nanoscale chemical and microstructure analysis has shown that gangue elements (byproducts from raw ore) partition into the remaining oxide regions. They are probed in part by energy dispersive spectroscopy and atom probe tomography. The APT specimens were prepared using the site- specific lift-out method at the wüstite-iron interface in a sample partially reduced for five minutes. The laser-pulsing mode was used at a wavelength of 355nm, laser energy of 40pJ, and a laser pulse frequency of 200kHz. Findings from the HPR sample are reconstructed into 3D atom maps and data analysis, shown in Figure 4. From the atom probe data, we can observe the highly crystalline nature of the reduced iron showing a pure iron phase from HPR; as well as silicon segregation to the interface between wüstite and iron, which is difficult to resolve with other analytical techniques [5].

What’s next: embracing green hydrogen?

DR: A growing number of academic and R&D professionals are recognizing that future steelmaking will use approaches where hydrogen is used as a reductant for iron ores. Hydrogen using renewable energy will remain a bottleneck in research for a couple of decades, or so. Fundamental to taking a sustainable approach is the use of green hydrogen, generated by renewable energy or from low- carbon power. [9] We must continue pursuing a hybrid approach that allows researchers to take advantage of the characteristics and kinetically beneficial aspects of both DR and HPR. Remember: Iron- and steelmaking produce 7% to 9% of humanity’s hazardous emissions due to the use of carbon for the reduction of iron ores. I and my colleagues urge researchers and the broader community to take advantage of the small window of opportunity that we have.

A very illuminating conversation with Professor Raabe! Certainly, research into the different reduction mechanisms for iron ore is an important part of finding lower-carbon ways to keep up with the increasing demand for steel without compromising our environment. I was lucky enough to hear Professor Raabe speak on this topic at the Fall Meeting of the Materials Research Society in Boston, and he passionately made the point that if you care about clean energy, you should be researching iron smelting. You should be indeed! With 7-9% of human-responsible greenhouse gas emissions being directly attributable to steel production, this is an absolutely critical area where we can make big gains with new processes. Atom probe tomography is already providing critical understanding of the reduction efficiency and mechanisms for both H-DRI and HPR, I really couldn’t agree more that this is an opportunity for materials scientists to make huge strides in understanding which can make a big impact for climate change.

Dierk Raabe, managing director at the Max Planck Institute for Iron Research (Düsseldorf, Germany), studied music (conservatorium Wuppertal), and metallurgy and metal physics (RWTH Aachen). After earning a doctorate in 1992 and habilitation in 1997 (RWTH Aachen), he worked at Carnegie Mellon University (Pittsburgh) and at the National High Magnet Field Lab (Tallahassee). He joined the Max Planck Institute in 1999. Raabe’s interests include phase transformation, alloy and segregation design, hydrogen, sustainable metallurgy, computational materials science, and atom probe tomography. He received the Leibniz Prize (highest German Science award) and two ERC Advanced Grants. The Max Plank Institute uses CAMECA’s LEAP 3000 and LEAP 5000 instruments to generate compositional data on a variety of materials systems.

Dierk Raabe, managing director at the Max Planck Institute for Iron Research (Düsseldorf, Germany), studied music (conservatorium Wuppertal), and metallurgy and metal physics (RWTH Aachen). After earning a doctorate in 1992 and habilitation in 1997 (RWTH Aachen), he worked at Carnegie Mellon University (Pittsburgh) and at the National High Magnet Field Lab (Tallahassee). He joined the Max Planck Institute in 1999. Raabe’s interests include phase transformation, alloy and segregation design, hydrogen, sustainable metallurgy, computational materials science, and atom probe tomography. He received the Leibniz Prize (highest German Science award) and two ERC Advanced Grants. The Max Plank Institute uses CAMECA’s LEAP 3000 and LEAP 5000 instruments to generate compositional data on a variety of materials systems.

Figure 4: Atom probe tomography (APT) analysis of the wüstite-iron interface in the partially hydrogen plasma-reduced sample after 5 min exposure time. (a) Cumulative field evaporation histogram with the (011) pole of the reduced iron (the arrows indicate the position of the interface); (b) spatial distribution map analysis showing the {011} lattice plane of the reduced iron; (c) three-dimensional atom probe tomography maps of iron and oxygen, and the wüstite-iron interface is marked by a 20 at.% oxygen isoconcentration surface; concentration profiles of (d) iron and oxygen, as well as (e) silicon relative to the position of the wüstite-iron interface. [5] [8]

References

[1] Statistica, Statista Research Department, “Crude steel production worldwide 2012-2021,” April 2022.

[2] YouTube, Metallurgy Guru – Sustainability Materials Science, “Sustainable Metallurgy and Green Metals,” June 2020, via University of Groningen, “Green steel made with hydrogen as reductant Prof. Dierk Raabe, Max-Planck Institut für Eisenforschung, Düsseldorf, Germany,” April 2022.

[3] Se-Ho Kim et al., “Influence of microstructure and atomic-scale chemistry on the direct reduction of iron ore with hydrogen at 700°C,” Acta Materialia, June 2021.

[4] World Steel Association, “Climate change and the production of iron and steel,” p. 3, 2021.

[5] I.R. Souza Filho et al, “Sustainable steel through hydrogen plasma reduction of iron ores: process, kinetics, microstructure, chemistry,” Acta Materialia, July 2021.

[6] International Energy Agency, “Iron and Steel Technology Roadmap,” p. 13, 2020.

[7] CAMECA-Nature Research Custom Media webcast, “Advancements in the development of green steel — making green steel with hydrogen,” with Professor Dierk Raabe, Max-Planck Institut für Eisenforschung, Düsseldorf, Germany, November 2022.

[8] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “OECD HIGHLIGHTS: Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060 – Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequence,” p. 15, October 2018.

[9] I.R. Souza Filho et al, “Green steel at its crossroads: hybrid hydrogen- based reduction or iron ores,” Journal of Cleaner Production, March 2022.

[10] Based largely on website content by Dierk Raabe, professor at the Max Plank Institute for Iron Research, “Atom Probe Tomography.”

Authors: Dierk Raabe (Managing Director at Max Planck Institute), Katherine RICE (Applications Lab Manager)