Here in the demo lab, we’ve seen interest growing recently in applying atom probe tomography (APT) to additively manufactured materials, particularly metals. Over the past few years we’ve had the opportunity to analyze nickel-based alloys such as nickel aluminum bronze [1], aluminum alloys [2] and several more. It’s been a lot of fun, but also resulted in a few high quality publications from our user base. Additive manufacturing (AM), or 3D printing, is an emerging technology used to create 3-D mechanical parts, layer-by- layer, utilizing geometry as the only input. With this new technology, rapid prototyping using AM has already reduced design cycle time and manufacturing development costs. There are several advantages here in addition to time savings: this can be employed to create parts on-demand to reduce the need and cost to keep inventory of replacement parts. Additionally, using a bottom-up printing approach can help in geometries that require complex machining, such as interior voids for heat sinks. One of the leading laboratories in this area is the Northwestern University Center for Atom Probe (NUCAPT). Here we sit down with Dr. Amir Farkoosh of NUCAPT to talk about his work in additively manufactured alloys, and provide some insight into how atom probe can provide information into the microstructure and hydrogen embrittlement behavior of new alloys. Dr. Farkoosh is always a welcome visitor to our lab, but I’d like to give him the opportunity to share some of this incredible work here for the blog. At NUCAPT, Dr. Farkoosh uses Atom Probe Tomography (APT) mainly in a correlative manner or in combination with other characterization techniques, analytical theory, and computer simulations. In the case of aluminum alloys, for instance, these alloys are generally strengthened with nanoprecipitates with different compositions and crystal structures.

KR: What makes additively manufactured alloys special, and how are they suited for analysis with APT?

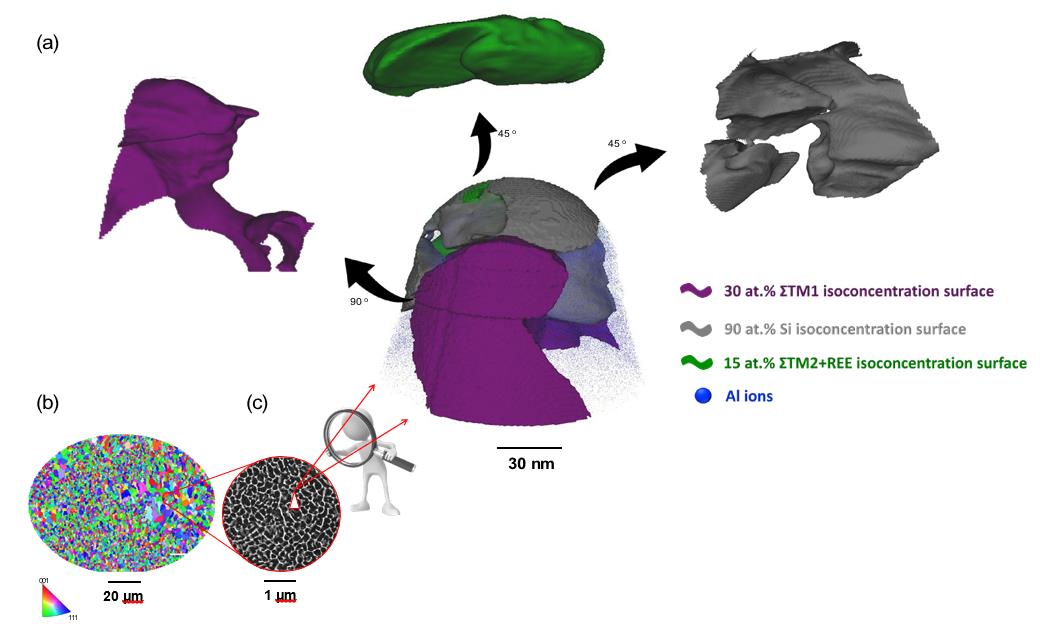

AF: Additive manufacturing enables significantly higher cooling rates than conventional manufacturing methods, resulting in microstructure development at a drastically smaller length scale. Consequently, AM alloys are particularly well-suited for examination using APT in comparison to conventionally produced alloys. In additively manufactured materials, most of the microstructural features are orders of magnitude smaller, several of which can be imaged in a single APT specimen. For instance, a single APT reconstruction in Fig 1 reveals the nature of a complex intertwined eutectic structure with four different phases directly solidified from the liquid state in one of my high strength NUAdd alloys [3], which remain ultra- strong at both ambient and high temperatures.

Figure 1: (a) 3D-APT reconstructions displaying the as-printed nano-structure of a heat-resistant ultrahigh strength NUAdd alloy produced via selective laser melting (SLM). This aluminum alloy is developed specifically for additive manufacturing at NUCAPT. The reconstructions reveal the nature of a complex intertwined eutectic structure made of four different phases, directly solidified from the liquid state. The two intermetallic phases and the Si phase are delineated with iso- concentration surfaces with concentration values indicated in the figure; ΣTM1 denotes a mixture of transition metals and ΣTM2+REE denotes a mixture of transition metals and rare-earth elements. (b) EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) map displaying the grain structure of the as-printed alloy. Grains are reinforced with the eutectic phase as shown in the SEM micrograph in (c).

APT data are ideal for direct comparison with atomistic computer simulations and modeling, to understand the microstructures and their dynamics on an atomic scale. Hence, my APT results are often complemented with density functional theory calculations and integrated to correlate processing, micro/nanostructures, and properties. This integration follows the fundamental paradigm of materials science and engineering, specifically focusing on the relationships between micro-/nanostructures and physical and mechanical properties.

KR: Why research aluminum alloys in relation to additive manufacturing?

Compared to steels, titanium alloys, and superalloys, aluminum alloys have experienced a slower adoption in AM despite attractive properties such as low density, high strength, and good corrosion resistance. To date, only a limited number of aluminum powders suitable for demanding, high-stress, or high- temperature applications are commercially available for AM.

There are a few reasons for this: current commercial aluminum alloys are much more difficult to process with the common AM techniques when compared to, for example, low-carbon steels or stainless steels. Hot-cracking susceptibility is a major issue. Commercial alloys, except for some cast alloys, crack during printing and should be modified significantly in order to enhance printability; or new alloys should be designed from scratch with good inherent printability, which by itself is an extremely challenging but rewarding endeavor.

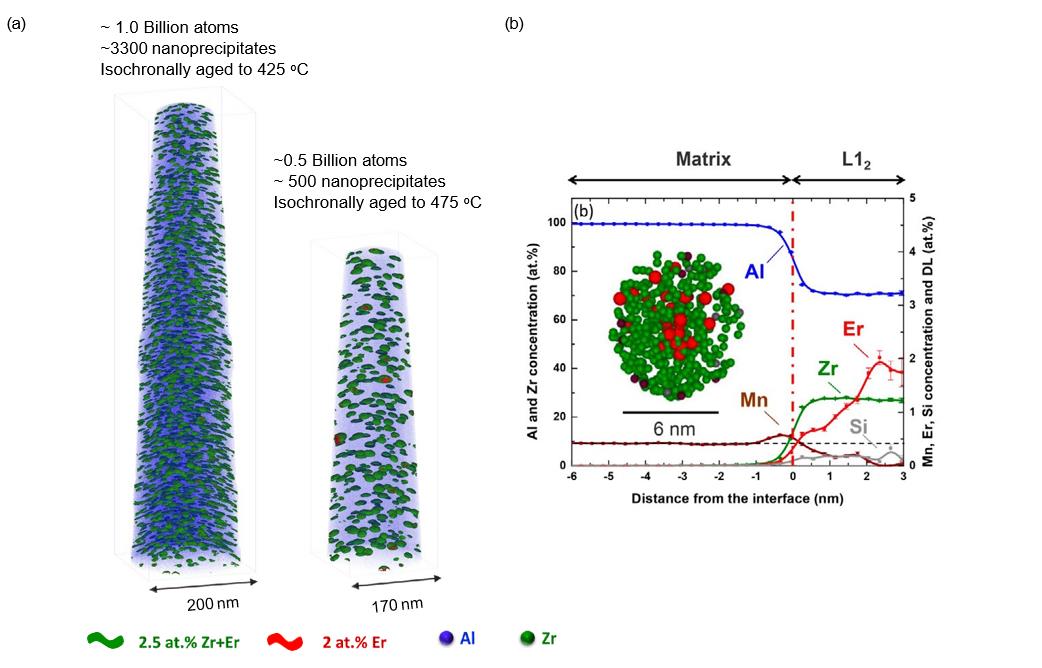

Another major problem with aluminum alloys, specifically those produced additively, is that existing commercial aluminum alloys are unusable above ~250C, due mainly to the rapid coarsening/dissolution of their fine scale strengthening precipitates [4]. To overcome this problem, in the past, we have utilized coarsening- resistant L12-nanoprecipiates, Fig. 2, to increase the operation temperature of conventional aluminum alloys up to 400 C. I employ a similar approach in designing heat-resistant aluminum alloys for AM.

Figure 2: 3D-APT reconstructions of an Al-0.5Mn-0.09Zr-0.05Er-0.05Si alloy after isochronal aging from the as-cast state to 425 °C (peak hardness) and to 475 °C (slightly overaged), showing the core-shell L12-nanoprecipitates delineated with 2.5 at.% (Zr+Er) iso-concentration surfaces. Only 1% of the Al atoms are displayed for clarity. (b) Proximity histogram [3] of the same alloy after isochronal aging from the as-cast state to 475°C, computed from the datasets displayed in (a), utilizing the 2.5 at.% (Zr+Er) iso- concentration surfaces. The detection limits (DL), defined as one atom per proxigram bin, are too small to be visible on the proximity histograms. The matrix/L12 interface (vertical dot-dash red lines) is defined as the inflection point of the Al concentration profile [5].

KR: What can you share about your research on ultra-strong aluminum alloys?

AF: The long-term goal of my research is designing and studying fundamentally a series of low-cost, high-strength precipitation-hardened aluminum alloys that are usable at both ambient and temperatures as high as 427° C. Over the last few years, I have embarked on developing novel aluminum alloys for additive manufacturing, NUAdd Alloy Series, which are strengthened with multiple populations of precipitates, utilizing similar alloy design principles. My interest lies in: 1) exploiting the unique characteristics of AM to develop advanced high-strength aluminum alloys tailor-made for AM, with mechanical and physical properties exceeding those of their conventional counterparts, and 2) overcoming the generic challenges associated with the AM of existing aluminum powders.

I take a materials-by-design, or first-principles, approach to alloy design for AM, utilizing integrated computational materials engineering combined with experiments and physical simulations of the AM processes. Some of my design considerations for AM alloys are printability, cost, ductility, and strength at ambient and high temperatures. Additive manufacturing of ultra-strong precipitation- hardened aluminum alloys refers to the use of AM in creating aluminum-based materials that possess exceptional strength and are reinforced through a process called precipitation hardening. These advanced aluminum alloys are engineered for use in applications that involve elevated temperatures, making them suitable for both high-temperature and standard (ambient) temperature environments.

KR: Hydrogen embrittlement is a hot topic in atom probe these days. How is hydrogen embrittlement a factor in the manufacture or design of these alloys?

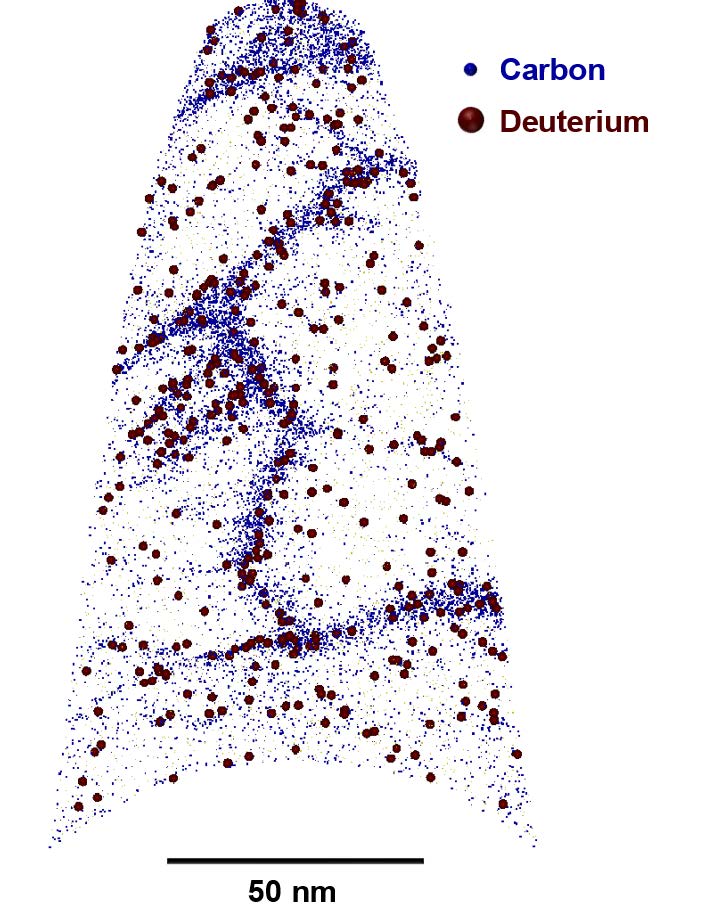

Hydrogen embrittlement, HE, is of concern in many applications, such as hydrogen energy systems, automotive, aircraft, marine, bridges, and nuclear reactors. Exposure of metals and alloys to hydrogen during manufacturing, storage, or service – even a relatively small average concentration of a few atomic parts-per-million – can embrittle structural materials. Aluminum is more resistant to HE compared to, for instance, stainless steels or high- chromium martensitic steels. In fact, the susceptibility of steels to embrittlement increases as their strength increases, and can potentially be a bigger problem in the case of additively- manufactured steels as they possess a high number density of defects. In a separate study on AM of steels, I utilize APT to understand how atomic-scale structures relate to brittleness when exposed to hydrogen by observing individual hydrogen atom distributions within the nanostructure of AM stainless steels as illustrated in Fig. 3. I intend to conduct similar studies on my NUAdd alloys.

Figure 3: A 3D atom-probe tomographic (APT) reconstruction of an additively manufactured QT17-4+ stainless steel provides convincing evidence for deuterium atoms being trapped within carbon-rich regions (i.e., austenite/martensite interfaces, lath martensite boundaries and perhaps epsilon carbides). The APT analyses are conducted at 60K in the voltage pulsing mode after electrochemically charging the specimen with deuterium. Electrochemical deuteration was employed instead of hydrogenation to enhance the accuracy of compositional analyses with APT. Deuterium is a stable isotope of hydrogen, also known as heavy hydrogen [6].

KR: I look forward to seeing the results on the NUAdd alloys. Hydrogen embrittlement is a growing application area for atom probe, and it would be very interesting to see improvements in embrittlement resistance for newly engineering alloys, particularly AM. Ok, to wrap up, Dr. Farkoosh, what’s next for you and your team?

Materials are at the center of any major challenge we face. To build a future of clean energy, we need more efficient engines, solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries. Manufacturers need new materials to create more advanced products and replace materials subject to supply disruptions, such as rare earth elements. APT and AM technologies will enable the development of electric, fuel cell, and hybrid-

powered vehicles, supporting the global movement towards environmental sustainability. Expertise and a technology base in lightweight, high-strength AM alloys is an important part of reaching these goals.

For more, check out some of the references in this work on additive manufacturing:

[1] Dharmendra, C., Rice, K. P., Amirkhiz, B. S. & Mohammadi, M. Atom probe tomography study of κ-phases in additively manufactured nickel aluminum bronze in as-built and heat-treated conditions. Materials & Design 202, 109541 (2021).

[2] Zhou, L. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Zr-modified aluminum alloy 5083 manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. Additive Manufacturing 28, 485–496 (2019).

[3] A.R. Farkoosh, D.N. Seidman, “Additive manufacturing of ultra-strong precipitation-hardened aluminum alloys for high and ambient temperature applications,” Office of Naval Research, annual report (2023).

[4] K.E. Knipling, D.C. Dunand, D.N. Seidman, “Criteria for developing castable, creep-resistant aluminum-based alloys - A review,” Z. Metallk. 97(3) (2006) 246-265. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijmr- 2006-0042

[5] A.R. Farkoosh, D.C. Dunand, D.N. Seidman, “Solute-induced strengthening during creep of an aged-hardened Al-Mn-Zr alloy”, Acta Materialia 219 (2021) 117268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. actamat.2021.117268

[6] A.R. Farkoosh, N. Eliaz, D.N. Seidman, “Influences of cohesion enhancing elements, impurities and hydrogen/deuterium at grain boundaries and heterophase interfaces on embrittlement of additively manufactured steels,” NSF-BSF, annual report (2023).

About NUCAPT:

The Northwestern University Center for Atom-Probe Tomography (NUCAPT) is an educational research facility at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 2004 by David Seidman, NUCAPT provides instrumentation, expertise, and services for materials characterization at the atomic scale, in 3D, via APT and related techniques. Research applications include local composition at surfaces, buried interfaces, and precipitates, compositional gradations, dopant profiles, and nanostructures in metallic materials, nanowires and semiconductor devices, quantum wells, thin-film, fuel cell barrier layers, biominerals and hybrid materials, nanomaterials for catalysis and environmental remediation, nuclear, geology, and planetary sciences, as well cultural heritage materials such as ancient glass and paint pigment. NUCAPT is open to researchers at all levels, including high-school interns, undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate students from Northwestern University, as well as external users from other universities, industry, non–profits, and government laboratories. For more information, visit nucapt. northwestern.edu/NUCAPT.

To get familiar with Atom Probe Tomography in less than 3 minutes, watch our whiteboard animation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CXiDO4vjfVg

Authors: Dr. Amir FARKOOSH (Post-Doctoral Researcher Northwestern University Center for Atom Probe (NUCAPT))

Other Participants/Contributors: Katherine RICE (Atom Probe Tomography Applications Lab Manager)